The price of factory farmed pork is seemingly cheap if you only look at the supermarket shelf price. However, the stark reality is that the true costs of factory farming are felt by the health of animals, farmers, consumers and the environment, all of which suffer because of intensive industrial production.

Globalised Food

Democratic, localised control of food is being eroded by the economic stranglehold of global food markets through large agribusiness and biotech corporations. A blinkered focus on profit and shareholder dividends does not, and will not sustainably feed a growing global population. Fewer and fewer corporations control the sale of higher value products and processed food to burgeoning markets while access to healthy food for the most vulnerable is becoming increasingly difficult.

UK case study: cheap imports

Cheap meat found on UK supermarket shelves comes with hidden costs that are not reflected in the purchase price. The majority of this cheap meat is imported and can only be produced at such low costs by disregarding animal welfare laws, over-using antibiotics and polluting the air and water. Around 50% of UK pigs are raised in high welfare systems, making it more expensive, but better for animals, human health and the environment. However 53% of our pork is now imported from the EU, and 70% of those imports have been produced in conditions that would be illegal in the UK.[1] This means that UK farmers are feeling the competitive pressure from these low cost, low welfare imports, so are increasingly forced to either intensify (and lower welfare standards), work to contract, or simply shut down.

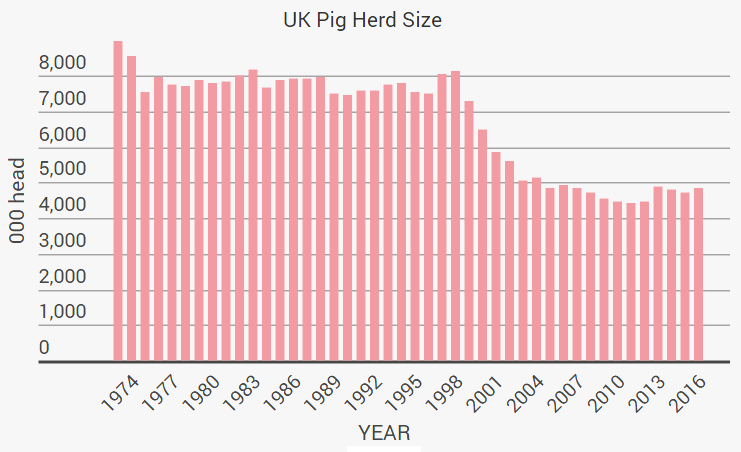

Although sow stalls (narrow steel cages that confine sows) have been banned in the UK since 1999, there is only a partial ban in the EU, meaning sows can spend up to 10 weeks per year in one of these individual, cramped cages, where they cannot even turn around. Because sow stalls do not allow pigs to behave naturally they induce severe stress, causing physical and psychological damage. Importing cheap pork from these European factories has lead to a 40% decline in the UK pig herd since 1999.[2]

How did we get here?

Farming has always exerted a strong influence on the rural landscape and its people; shaping it physically and providing economic stability and a way of life for families and communities. With the expansion of big agribusiness however, many rural communities have started to suffer as small farms cease to be financially viable and rural life is diminished.

Technological advances in animal agriculture, due to their high cost, have meant that intensive farms must produce at maximum capacity to make a profit, maintaining high production levels even at times of low demand. Further, the vertical integration of the meat market means that products move within the supply chains of big agribusiness.[3] In other words, big farms do not utilise local meat packers, processing plants, slaughterhouses and equipment dealers. These local and independent businesses, however, are vital for providing employment, investment and stability to rural communities.[4]

Corporate takeover

76% of the UK food market is controlled by just four companies.[3] This monopolised market is both costly and unhealthy; the concentrated nature of the market means that our access to the food supply, and the price that we pay for it, is dependent on the decisions of a few key corporations.[5] In livestock production, a company may be involved with every step of its food production, from contracting farmers to raise the animals, to slaughtering, packaging and delivering to supermarkets.

Solution: food sovereignty

By outsourcing our meat production to farms elsewhere in the world, we risk becoming reliant on a supply over which we have little control, putting our food security at risk. Consumers are at the end of a complex and long supply chain. This means that a bad harvest or epidemic hundreds or thousands of miles away can affect food prices in the UK. In 2017 for example, the price of courgettes quadrupled due to cold weather in Spain and Italy.[6] By producing and purchasing our pork locally from high welfare British farms, the price of pig meat can be made more consistent, and the supply reliable and shock proof. It also becomes easier to regulate farms producing pork when they are decentralised, and to ensure traceability and high standards of welfare.

Consumers in the UK can look out for high welfare labels when buying their pork: Outdoor Bred, RSPCA Assured, Free Range, or best of all, Organic. Find out more here.

‘Food sovereignty’ presents a framework for creating an alternative to the dangerous trend of increasing corporate control over food and the economic, social and environmental consequences it brings. The term was coined in 1996 by members of global peasant organisation La Via Campesina, the world’s largest social movement, incorporating 200m members from 183 organizations in 88 countries.

In its most basic sense food sovereignty asserts the right of people to define their own food systems by:

- Focusing on food for people: The right to food which is healthy and culturally appropriate is the basic legal demand underpinning food sovereignty. Guaranteeing it requires policies which support diversified food production in each region and country. Food is not simply another commodity to be traded or speculated on for profit.

- Valuing food providers: Many smallholder farmers suffer violence, marginalisation and racism from corporate landowners and governments. People are often pushed off their land by mining concerns or agribusiness. Agricultural workers can face severe exploitation and even bonded labour. Although women produce most of the food in the global south, their role and knowledge are often ignored, and their rights to resources and as workers are violated. Food sovereignty asserts food providers’ right to live and work in dignity.

- Localising food systems: Food must be seen primarily as sustenance for the community and only secondarily as something to be traded. Under food sovereignty, local and regional provision takes precedence over supplying distant markets, and export-orientated agriculture is rejected. The ‘free trade’ policies which prevent developing countries from protecting their own agriculture, for example through subsidies and tariffs, are also inimical to food sovereignty.

- Putting control locally: Food sovereignty places control over territory, land, grazing, water, seeds, livestock and fish populations on local food providers and respects their rights. They can use and share them in socially and environmentally sustainable ways which conserve diversity. Privatisation of such resources, for example through intellectual property rights regimes or commercial contracts, is explicitly rejected.

- Building knowledge and skills: Technologies, such as genetic engineering, that undermine food providers’ ability to develop and pass on knowledge and skills needed for localised food systems are rejected. Instead, food sovereignty calls for appropriate research systems to support the development of agricultural knowledge and skills.

- Working with nature: Food sovereignty requires production and distribution systems that protect natural resources and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, avoiding energy-intensive industrial methods that damage the environment and the health of those that inhabit it.

Footnotes

- The Pig Site, (2011), Analysis of UK Pork and Pork Products Import Trade from 2013

- AHDB, (2016), UK Pig Herd

- Friends of the Earth, (2014), Broken Food Chains

- Friends of the Earth, (2015), From Farm To Folk

- ETC Group, (2013), Putting the Cartel before the Horse …and Farm, Seeds, Soil, Peasants, etc.

- The Daily Telegraph, (2017), Courgette crisis

Animal Welfare

Industrial, indoor factory pig farming is designed to produce as much yield and profit as possible. The animals are reduced to units of production, rather than sentient beings with physical and psychological needs. The drive for efficiency and cost-effectiveness conflicts heavily with animal welfare.

Most pigs raised for meat to be sold in the UK are suffering in factories that cram the animals into barren, overcrowded sheds where they are unable to express natural behaviour such as running, playing, rooting and wallowing. They are routinely dosed with antibiotics, just to keep them alive in such awful conditions.

Sow stalls (gestation crates)

Sow stalls are small, individual metal cages used to confine pregnant pigs (sows) for up to a month at a time. The sow is unable to turn round, lying on a concrete, slatted floor, illegally deprived of straw or other bedding material for comfort.

The stress and frustration caused by confinement drives pigs to bite at the bars of their enclosures so incessantly that blood coats the front of their crates. The confined quarters also result in pressure sores and ulcers from not being able to move, untreated abscesses and various infected wounds worsened by the bodyweight of pregnant pigs.

In most European countries (where over 50% of the pork sold in the UK comes from) sow stalls are permitted for four weeks in each gestation period, which can amount to ten weeks of each year. Buying imported pork, therefore, is likely to mean buying meat from factories that use sow stalls. In the UK, this type of crate is officially banned.

Farrowing crates

Farrowing crates, allowed in both the UK and most EU countries, are slightly larger stalls that allow minimal space for sows to lie down while they suckle their piglets. They cannot turn around to nurse them which is a strong instinct in mother pigs and all animals. Sows are usually moved to farrowing crates a week before giving birth and typically stay there day and night until the piglets are weaned, a total of five weeks in each pregnancy cycle, or eleven weeks a year. These crates have been banned in Sweden, Norway and Switzerland. Sows in countries from which we import over 50% of the pork consumed in the UK, can spend up to 20 weeks each year in sow stalls and farrowing crates.

Sows in farrowing crates exhibit similar physical and psychological symptoms to those in sow stalls, with the added stress of being prevented from performing their natural behaviours of foraging and nesting before giving birth. Piglets stay with their mothers for three or four weeks, compared to the 13-17 weeks that would occur under more natural conditions.[1] Sows are also prevented from moving away from their piglets as they do on outdoor farms if, for example the piglets bite her teats. For this reason, it is common practice to clip piglets’ teeth.

Growing Pigs

In animal factories, growing pigs are often kept in barren, overcrowded pens. EU animal welfare laws require that pigs have access to adequate bedding and that their tails are not routinely docked. However, these regulations are widely ignored in pig factories.

Tail biting occurs when pigs are stressed and frustrated by being permanently confined in overcrowded pens on bare concrete floors, and are unable to express their natural behaviour. In these intensive systems, pigs develop stress-induced behaviour, leading them to bite the tails and other limbs of their pen mates. The law in both the EU and the UK says that tail docking can only be carried out if the reasons for tail biting have been addressed. If pig farmers kept their animals in accordance with the law which prescribes (1) sufficient fresh straw or similar enrichment to allow pigs to express natural behaviours such as rooting, manipulation and nesting (2) adequate space allowances so that aggression and stress are not induced by overcrowding – tail docking would not be necessary. An estimated 94% of piglets in the EU have their tails illegally docked before they are seven days old.[2]

EU legislation

Despite EU legislation, the systematic mutilation of pigs in the form of tail docking, teeth clipping and castration is seen routinely throughout Europe.

CIWF has found numerous and persistent cases of non-compliance with EU legislation for animal welfare in member states across the EU. In 2009, CIWF found that 100% of farms visited in the Netherlands and Spain had a significant number of tail-docked pigs present.[3] A follow up report in 2014 found that problems still persisted in the two member states, as well as the UK, Poland, the Netherlands, Italy, Ireland and France.[4]

In 2010, the Humane Society conducted an undercover investigation of a Smithfield breeding facility in order to verify Smithfield’s pledge to phase out its use of sow stalls. The investigation revealed a pattern of systematic abuse against the pigs, and documented abuse far beyond the misery of the extreme confinement of sow stalls. The workers at the breeding plant were seen to treat the pigs with neglect and malice, with the investigator recounting a pig being stunned and thrown into waste bin whilst alive and breathing.[5]

In another investigation carried by CIWF in Ireland, pigs were found living in inches deep excrement, covered in scratch marks and open wounds from stress-induced fights, widespread tail-docking, as well as weaker pigs spread across the corridors, being left to die.[6]

The poorly ventilated quarters, rife with bacteria and filth, has been shown to cause lung damage and pneumonia among pigs from animal factories, with “40-80% of pigs, depending on conditions, showing lesions in their lungs at the time of slaughter”.[7]

High welfare alternatives

There are alternatives to the conditions described above. Pork with high animal welfare labels is sourced from farms where pigs are outdoors – or indoors with plenty of bedding, space and fresh air – and are able to express natural behaviours such as running, rooting, nesting, wallowing and playing.

Organic pigs are kept in conditions that allow them to express their natural behaviour. The use of the European Union Organic logo is mandatory for all pre-packaged organic products that have been produced in any EU Member State. The Soil Association Organic Standard is one of only a few schemes that chooses to “set its standards even higher than the EU organic standard”. There are 8 other approved UK organic certification bodies.

Free range pigs are born outside in fields, and they remain outside for their whole lives. They are provided with food, water and shelter and are free to roam within defined boundaries. Free range pigs have very generous minimum space allowances, which are worked out according to the soil conditions and rotation practices of the farm. Breeding sows are also kept outside with access to hutches with straw.

Outdoor bred pigs are born outside in fields, where they are kept until weaning (normally around 4 weeks) and moved indoors. Breeding sows are kept outside in fields for their productive lives. The pigs are provided with food, water and shelter with generous minimum space allowances. ‘Outdoor reared’ is a similar system, but the piglets usually have access to the outdoors for up to 10 weeks before being moved indoors.

RSPCA Assured (previously called Freedom Food) is the RSPCA’s labelling and assurance scheme dedicated to improving welfare standards for farm animals. About 30% of pigs reared in the UK are reared under this label. The scheme covers both indoor and outdoor rearing systems and ensures that greater space and bedding material are provided. The RSPCA assesses farms to strict welfare standards, which you can read more about here.

Footnotes

- CiWF, (2006), Animal Welfare Aspects of Good Agricultural Practice: pig production

- CiWF, (2013), Statistics: pigs

- CiWF, (2009), Pigs Farming in the EU

- CiWF, (2014), Lack of Compliance with the Pigs Directive continues

- The Humane Society, (2010), Undercover at Smithfield Foods

- CIWF (2013), Irish Pig Farm Investigation

- Constable, P. D., Gay, C. C., Hinchcliff, K. W., & Radostits, O. M. (2007). Veterinary medicine: a textbook of the diseases of cattle, sheep, pigs, goats and horses. The Canadian Veterinary Journal as quoted in: Sustainable Table, Animal Welfare

Antibiotics Overuse

We are facing a future when antibiotics will be ineffective and simple routine operations too dangerous to undertake. This is partly because antibiotics have been misused in factory farms to compensate for overcrowded, unhealthy conditions which has led to the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistant diseases that pass from animals to humans.

Antibiotics & Agriculture

The overcrowding and lack of bedding in factory farms, which leads to tail biting, as well as the stress caused by early weaning of piglets before their immune systems have developed, mean that routine doses of antibiotics are required for factory farms to operate profitably.[1]

In many countries, more antibiotics are given to healthy animals than are given to sick people. Across the world at least half of all the antibiotics used are dispensed for livestock.[2] In the UK, approximately 25% of all antibiotics are given to pigs in animal factories just to keep them alive.[3]

Resistance

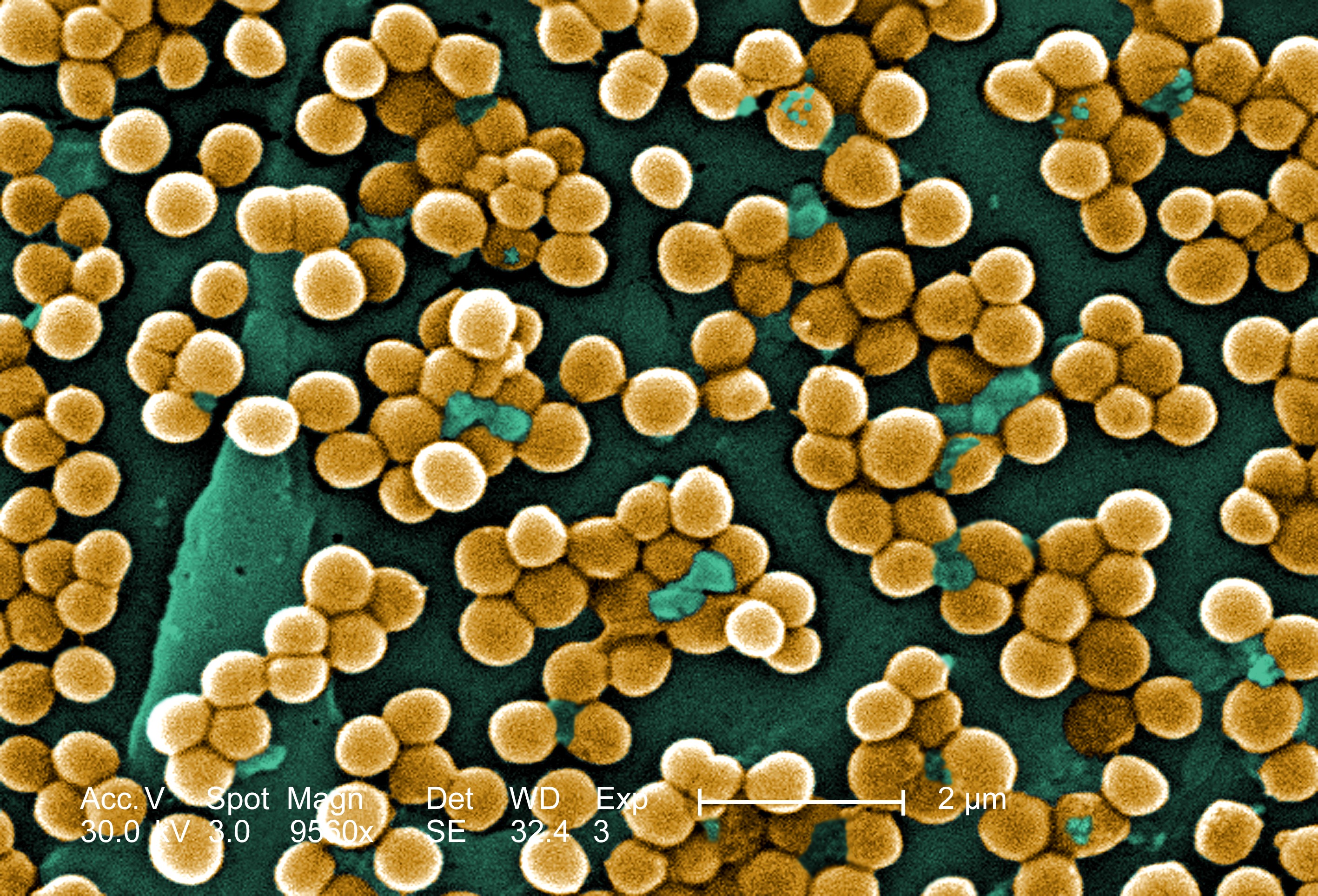

The latest government Review on Antimicrobial Resistance reports that the overuse of antibiotics in pig factories is a significant cause of antibiotic resistance in many human diseases.[4] For some bacterial infections such as Campylobacter and Salmonella, farm antibiotic use is the principal cause of resistance in human infections. For other infections, like E. coli and enterococcal infections, farm antibiotic use significantly contributes – or has significantly contributed – to the human resistance problem, and that livestock-associated strains of MRSA infecting humans are a developing problem; a direct result of the high use of certain antibiotics in farm animals.[5]

Overuse of antibiotics in animals has caused the emergence of a new livestock strain of antibiotic-resistant MRSA, CC398, which passes to humans.[6] In 2015, an investigation by The Guardian revealed that the “livestock-associated superbug MRSA CC398, which originates in animals, has been found in pork products sold in Sainsbury’s, Asda, the Co-operative and Tesco. Of the 100 packets of pork chops, bacon and gammon tested by the Guardian in 2015, nine – eight Danish and one Irish – were found to have been infected with CC398.”[7]

Research in the USA found that motorists and those living near the roads used for transporting intensively farmed chickens and pigs to slaughter are at significantly greater risk of exposure to airborne pathogens and antibiotic-resistant bacteria.[8] A 2014 study found that flies spread antibiotic-resistant bacteria from animal factories to nearby communities.[9]

In November 2015, a gene was discovered in factory farmed pigs in China that enables diseases to become resistant to Colistin, an antibiotic of ‘last resort’ in human medicine also commonly used in intensive pig farms.[10][11] There have been no new antibiotics created since 1987, and, although promising, the recently discovered Teixobactin is still in the prototype phase and could take several years to be approved and reach the market.[12]

In September 2016 a survey of low welfare (Red Tractor) pork in UK supermarkets by the Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics found that 63% of the samples were contaminated with antibiotic-resistant E.coli, bacteria that cause life-threatening kidney infections and blood poisoning. The survey also found resistance to the antibiotic Trimethoprim on 51% of pork and poultry samples from seven major UK supermarkets.[13]

Dr Margaret Chan, head of the World Health Organization, says: “Growing global demand for meat, especially when met by intensive farming practices, contributes to the massive use of antibiotics in livestock production.”[14]

Former Chief Medical Officer, Sir Liam Donaldson has said: “Every inappropriate use of antibiotics in animals is potentially signing a death warrant for a future patient.”[15]

What can we do?

We can help reduce the use of antibiotics in animal farming by joining a growing movement to avoid meat from animal factories that breed antibiotic resistant bacteria, and instead only buy pork raised in high welfare conditions, either outdoors, or indoors with adequate space, bedding and fresh air, where the animals rarely need antibiotics. Pork from these high welfare farming systems is sold in the UK with the labels RSPCA Assured, Outdoor Bred, Free Range and Organic. Read more about labelling here.

Footnotes

- CIWF, (2013), Zoonotic Diseases, Human Health and Farm Animal Welfare

- The Pew Commission, (2011), Antibiotics and Industrial Farming

- Hockridge E., (2010), The Soil Association comments on Planning Application 9/2010/0311 – Foston pig farm

- O’neill J., (2015), Review on Antimicrobial Resistance: Antimicrobials in agriculture and the environment – Reducing unnecessary use and waste

- CIWF, (2013), Antibiotic resistance – The impact of intensive farming on human health: A report for the Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics

- CIWF, (2013), Antibiotic resistance – The impact of intensive farming on human health: A report for the Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics

- The Guardian, (2015), MRSA superbug found in supermarket pork raises alarm over farming risks

- Rule et al. (2008) Food animal transport: A potential source of community exposures to health hazards from industrial farming (CAFOs), Journal of Infection and Public Health, 1(1): 33-39

- Zurek, L. & Ghosh, A. (2014) Insects Represent a Link between Food Animal Farms and the Urban Environment for Antibiotic Resistance Traits, Applied and Environmental Microbiology 80(20): 3562 – 3567

- The Lancet, (2015), Antibiotic resistance threatens the efficacy of prophylaxis

- National Geographic, (2015), Apocalypse Pig: The Last Antibiotic Begins to Fail

- Daily Telegraph, (2016), First new antibiotic in 30 years discovered in major breakthrough

- Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics, (2016), Antibiotic-resistant E. coli on supermarket meat – a serious threat to human health

- Dr Margaret Chan, (2016), WHO Director-General addresses ministerial conference on antimicrobial resistance

- Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics, (2015), Antimicrobial resistance – why the irresponsible use of antibiotics in agriculture must stop

The Environment

The food system has become increasingly globalised, making the process of getting food onto our plates wasteful and destructive. It is estimated that all the food and drink consumed in the UK produces approximately 130 million tonnes of CO2eq per year, a fifth of the country’s total carbon emissions.[1]

The situation

- Intensive factory farming means that pigs are increasingly eating grains and soya rather than locally produced fodder or food waste. Imported genetically modified soya, grown on cleared Rainforest and Cerrado Forest in S America, contains residues of the herbicide Roundup which damages the health of the pigs. The cleared trees are burnt, and the soya is shipped 8,000 miles to Europe, adding to the alarming carbon cost of industrially farmed meat.[2]

- Factory pig farms produce waste that pollutes the air, sickening local residents, and contaminates rivers, lakes and the sea, causing fish kills and destruction of aquatic wildlife.[3]

- Industrial monocultures which supply pig feed depend on high inputs of fossil fuels, chemical fertilisers, herbicides and pesticides that poison local residents and destroy the natural nutrients in the soil.[4],[5].

Factory farming is all-too-often viewed as the cheap, efficient solution to feeding world, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. For every 100 food calories of edible crops fed to livestock, we get back just 30 calories in the form of meat and dairy; a 70% loss. In short, people are being forced to compete with farm animals for food.

In the past, pigs were fed on grass, forage crops or waste produced on the farm itself. Globally-sourced animal feed is now used instead.[7]

Now, according to the UN, 80% of the available arable land worldwide is currently being used solely for the production of livestock feed.[8] This is adding to food shortages, malnutrition and hunger. Land needed to grow the animal feed to support the rapidly expanding livestock industry has led to deforestation and land degradation.[8] The world’s economy is expected to quadruple by 2050, with livestock production accounting for a major share of this growth – resulting in unsustainable demands on natural resources.[8]

There has been an expansion of industrial soya farms, which has already displaced many small farmers in Latin America, destroying previously sustainable farming systems that worked in harmony with the existing ecosystem, and provided for families and local communities. Surveys by the UN and NGOs are revealing an increase in inequality and continuous land-grabbing by fewer and bigger corporations along with routine shocking murders of activists campaigning for the rights of small scale farmers.[5]

Food sovereignty and food security is under threat in many parts of the global south where resources are being used to produce cash crops for export to service debts to global banks. The profitability of soya production for agribusiness, and fragile land rights in Latin American countries has led to land grabbing by corporations, sometimes by violent means, to meet the demands of animal factories in Europe and elsewhere.[5]

What can be done?

Well managed pasture and grass-fed livestock farming is better for the environment, using fewer inputs which produce waste that is less harmful and in lower concentrations. The manure is not waste but a valuable soil nutrient. This means that soil quality is conserved, erosion and water pollution are less prevalent, better carbon sequestration takes place and biodiversity levels are preserved.[9] The use of compost and rotational grazing ensures that soils stay healthy and productive, whilst also providing natural pest and weed resistance in the face of climate change.[9] Scaling down livestock consumption in rich countries is the fastest and most effective response that we can make to reduce the environmental footprint of food production and to make more food available for human consumption.[10]

Footnotes

- WRAP & WWF (2011) The Water and Carbon Footprint of Household Food and Drink Waste in the UK

- Organic Consumers Association (2013) Climate Chaos: Boycott Genetically Engineered and Factory-Farmed Foods

- WWF (2016) Sustainable Agriculture: Impacts

- FAO (2013) World Livestock 2013: Changing disease landscapes

- WWF (2014) The Growth of Soy: Impacts and Solutions

- IPCC (2014) Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change

- FOE (2014) Broken Food Chains

- FAO (2013) Tackling climate change through livestock: a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities

- Environmental Working Group (2011) Meat Eater’s Guide to Climate Change and Health

- CIWF (2009), Beyond Factory Farming; Sustainable Solution for Animals, People and the Planet

Frequently Asked Questions

- 1· What is a ‘pig factory’?

- 2· What is a ‘high welfare’ farm?

- 3· Why do pig factories exist?

- 4· I thought that the UK had high minimum animal welfare standards. Is this not the case?

- 5· Are minimum welfare standards the same for all countries?

- 6· If your aim is to shut down big pig factories, won’t that put UK pig farmers out of business?

- 7· Why does high welfare meat cost me more?

- 8· What if I cannot afford to buy high welfare meat?

- 9· What are the impacts of pig factories on the environment?

- 10· What are the impacts of pig factories on our health?

- 11· What are the minimum animal welfare standards in pig factories?

- 12· But aren’t pig factories the only method of producing enough food for the future?

- 13· Where can I buy high welfare pork? Where is the best place to buy high welfare pork?

- 14· What’s the best high welfare pork? Does it have to be Organic?

- 15· How can I be sure that the meat I am buying does not come from a pig factory?

- 16· Wouldn’t it be better solution to not to eat meat at all?

- 17· What’s the difference between caged pigs, sow stalls, gestation crates & farrowing crates?

1· What is a ‘pig factory’?

Pig factories can be defined as intensive, indoor facilities in which pigs are kept on concrete slatted floors without straw or similar bedding, routinely tail docked and routinely given antibiotics. Mother pigs are confined in farrowing crates, too narrow for them to turn around, for five weeks in each pregnancy.

2· What is a ‘high welfare’ farm?

Pigs on high welfare farms, either outdoors or indoors with plenty of straw, are healthy and happy and do not need antibiotics. They are free to roam and express their natural instinctive behaviour such as rooting, nesting and playing.

3· Why do pig factories exist?

The aim of pig factories is to produce as much meat at the lowest possible cost possible to meet the rising global demand for cheap protein while making the largest profit. Livestock production has grown increasingly more industrialised compromising not only animal welfare but also our health, local economies and the environment.

4· I thought that the UK had high minimum animal welfare standards. Is this not the case?

UK minimum welfare standards are higher than those in many other EU countries, but farrowing crates (metal cages that restrict the mother pig’s movement and prevent her from nurturing her piglets) are allowed for 5 weeks in each pregnancy, or 2.5 months a year. Furthermore, many intensive systems in the UK have been found to be breaking welfare regulations by keeping pigs on bare concrete slats with no bedding, and routinely cutting off piglets tails to prevent biting.[6]

5· Are high welfare standards the same for all countries?

Below is a table comparing minimum welfare standards in the UK, EU & USA:

| Country | Sow Stalls | Farrowing Crates | Bedding | Antibiotics | Tail Docking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | not allowed | allowed for 5 weeks in each pregnancy, equivalent to 2.5 months a year | pigs must have access to straw or similar manipulable material. Widely ignored | not allowed to be given as growth promoter, 50% antibiotics used for animals mostly in intensive indoor systems | the law says that tails must not be docked routinely, the cause must be addressed first. Widely ignored |

| EU | allowed for four weeks in each pregnancy, equivalent to 2 months a year | allowed for 5 weeks in each pregnancy, equivalent to 2.5 months a year | pigs must have access to straw or similar manipulable material. Widely ignored | not allowed to be given as growth promoter, high use of antibiotics except Denmark and Sweden |

the law says that tails must not be docked routinely, the cause must be addressed first. Widely ignored |

| USA | permanent confinement in sow stalls permitted | no restriction | no legal requirement | can be used constantly in feed as growth promoter. 75% antibiotics used for animals mostly in intensive systems |

no restrictions |

6· If your aim is to shut down big pig factories, won’t that put UK pig farmers out of business? (and what will happen to the pigs?)

Shutting down pig factories would benefit high welfare UK farmers. Animal factories abuse animals in inhumane conditions and externalise costs onto the broader community (by antibiotic overuse, pollution and toxic stench), thereby unfairly outcompeting smaller, high welfare farmers and destroying local communities.

In addition, indoor spaces, presently used as animal factories, can easily be converted to ethical methods of production by providing more space, ample bedding and ideally access to the outdoors.

7· Why does high welfare meat cost me more?

High welfare pork often costs more than meat produced in pig factories because pork from animal factories carries five heavy costs that are not captured in the price:

- Threat to public health from superbugs caused by overuse of antibiotics

- Undermining of real farmers and rural economies

- Pollution of air and water which sickens local residents and destroys wildlife

- Animal abuse through confinement, overcrowding, mutilation, exploitation, neglect and denial of natural behaviours

- The globalisation of our livestock system and the resulting loss of food sovereignty

These costs never appear in grocery or restaurant bills, but they result in incalculable costs for the environment, local communities and future generations.

8· What if I cannot afford to buy high welfare meat?

You can reduce your intake of pork, bacon, ham and sausages to cover the extra cost of buying high welfare. For example, six sausages from an animal factory cost the same as five from a high welfare farm. And three rashers of bacon from an animal factory cost the same as two from a real farm.

Eating less, but better, meat is good for your health, and the impacts of over-consumption are well documented[1]. Eating less meat and cooking with cheaper cuts can save money on shopping bills, which makes it possible to buy high welfare without necessarily spending more. Here you can find some ideas on how to prepare and cook vegetarian meals and meals with cheaper cuts[2].

9· What are the impacts of pig factories on the environment?

Animal factories can produce meat cheaply because they do not pay the costs for natural resources they consume. In addition, they produce huge quantities of waste and greenhouse gases, contributing to climate change and polluting our land, air and water.[3]

10· What are the impacts of pig factories on our health?

Excessive quantities of antibiotics are used on animal factories. In the UK, approximately 25% of ALL antibiotics are given to pigs in animal factories just to keep them alive in the overcrowded, contagious conditions. In December 2015, a UK government report warned that overuse of antibiotics in intensive livestock production is a significant cause of antibiotic resistance in many human diseases.[4]

11· What are the minimum animal welfare standards in pig factories?

In animal factories, pigs suffer from confinement, isolation or overcrowding and the frustration of their natural behaviour. Minimum EU welfare standards require that pigs have access to adequate bedding and that their tails are not routinely docked. However these regulations are routinely ignored in pig factories. This is why it is so important to buy pork produced to the standards of a recognised assurance scheme. See here the different assurance standards in the UK and what they mean for animal welfare.

12· But aren’t pig factories the only method of producing enough food for the future?

The industrialisation of pork production in animal factories was ‘invented’ in the 1960s with the aim of using economies of scale to increase profit margins. However, this type of production is inefficient because of its high capital costs, and because it needs high input volumes of water, energy and imported feed. The system is also unsustainable and unethical because it relies on antibiotics to compensate for the barren, overcrowded and unhealthy conditions in which the pigs spend their lives.

Food for the future can be provided much more efficiently by growing crops for human consumption, instead of using those crops to feed livestock.[5]

13· Where can I buy high welfare pork? Where is the best place to buy high welfare pork?

You can buy pork with high animal welfare labels in the supermarket, so look for RSPCA Assured, Outdoor Bred, Free Range or best of all Organic. You can ask for high welfare meat at your local butcher or better still shop at your local farmers’ market, find high welfare online, or join a box scheme.

14· What’s the best form of ‘high welfare’ pork? Does it have to be classed as Organic?

We recognise different categories for high welfare pork (see our labelling system).

Organic is the only standard which offers not only higher animal welfare standards, but also environmental benefits in terms of waste management, residue, pesticides and fertilisers. The Organic standard also guarantees that no GMOs have been used in the feed.

15· How can I be sure that the meat I am buying does not come from a pig factory?

To avoid products that are falsely marketed as ‘high welfare’, it is best to look for meat that carries the official high welfare labels. Pork with these labels has been raised on high welfare farms, almost certainly in the UK, and farmers are inspected regularly to ensure they are complying with the standards fully.

Alternatively, check out our ‘questions to ask retailers’ when you can’t see a label on meat in your local butchers or farmers’ market.

16· Wouldn’t it be better solution to not to eat meat at all?

Farms Not Factories’ vision is a world without animal factories. We want to raise awareness about the true costs of cheap meat, but we recognise that for many people, going vegetarian or vegan is not an option. That’s why we are working to make it easier for the public to choose ethically produced pork through our supermarket labelling guide and High Welfare Pork Directory.

Livestock farming is not simply a means of production; like all food production it has a rich cultural and socio-economic history. It has shaped the British countryside and its rural communities. To lose traditional, small-scale livestock farms would be to lose a wealth of tradition, knowledge and practice.

It is important to remember that animals are not the only casualties of a globalised and industrial meat industry. Choosing to buy pork from sustainable and local farms is a vote for a world free from the social, environmental and health impacts of the industry on communities around the world. And in a world where food security and sovereignty are increasingly important, we can – if we do choose to eat meat – support local farmers by buying from farmers’ markets and local butchers.

17· What’s the difference between caged pigs, sow stalls, gestation crates & farrowing crates?

When talking about pigs in cages, we mean the use of sow stalls (also called gestation crates) and farrowing crates.

Sow stalls are narrow, steel cages that prevent the sow from turning around during pregnancy. They are illegal in the UK. There has been a partial ban in the EU since January 2013, which allows sow stalls to be used for up to 4 weeks in each pregnancy. However, a number of countries continue to be non-compliant on this ban.

Farrowing crates are also narrow, steel cages that prevent the sow from turning around during pregnancy. They are not illegal in the UK. Sows can be kept in farrowing crates just before they give birth, and remain there for up to 5 weeks. See our labelling guide to find out which UK labels use farrowing crates.

Footnotes

- Raphaely,T., Marinova,D. (2015) Impact of Meat Consumption on Health and Environmental Sustainability. Chapter 8 pp.131-177

- Boer,J. (2014) “Meatless days” or “less but better”? Exploring strategies to adapt Western meat consumption to health and sustainability challenges

- WWF (2016) Sustainable Agriculture: Impacts Tackling climate change through livestock, HSI (2011) Fact sheet: Factory farming in Mexico and CIWF (2009), Beyond Factory Farming; Sustainable Solution for Animals, People and the Planet

- O’neill J., (2015), Review on Antimicrobial Resistance: Antimicrobials in agriculture and the environment – Reducing unnecessary use and waste

- FOE (2010) Factory farming’s hidden impacts and FAO (2013) Tackling climate change through livestock

- CIWF (2013) Widespread breaches of pig welfare laws in the EU

Comments